QUAESTIONES QUODLIBETALES

The Star of Bethlehem

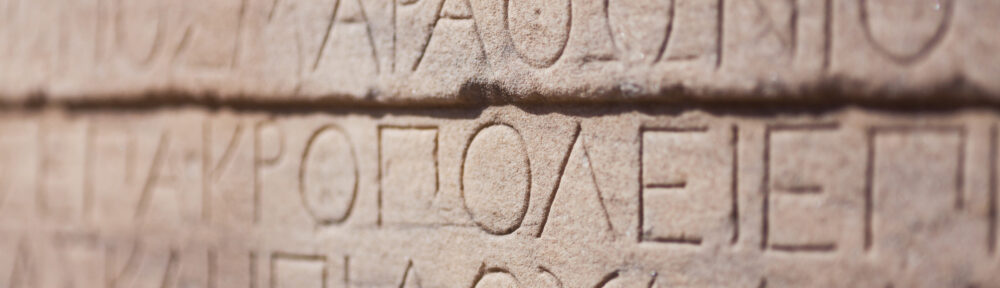

The story of the Star of Bethlehem is told by Matthew in the second chapter of his Gospel (2:2–12). In fact, Matthew refers to a star seen “at its rising” (ton astera en tè anatolè, τὸν ἀστέρα ἐν τῇ ἀνατολῇ). The tradition of the star as a comet comes from Giotto, who, having been impressed by the sight of Halley’s Comet, depicted it in the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua in the early 1300s. From then on, the star became associated with a comet.

The great astronomer Kepler, on the other hand, hypothesized that it was a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn aligned with the Sun, which he had personally observed. He calculated that a similar phenomenon occurred around 6–7 BCE, since this triple conjunction happens roughly every 794 years. The Jupiter-Saturn conjunction was already known in antiquity, especially in Babylon—the land of astronomers and astrologers—where the Magi likely originated.

In any case, whether it was a fixed star or a comet, it is extremely unlikely that it played any real role in the birth of Jesus. Bethlehem is only 7–8 km (about 4–5 miles) from Jerusalem—a distance far too small to be pinpointed by a celestial event. Halley’s Comet, for example, passes at a distance of about 63 million kilometers from Earth; Jupiter (which is closer to Earth than Saturn) is between 588 and 968 million kilometers away. A supernova (an exploding star—Newton himself witnessed one, SN 1054) would be at a distance of at least hundreds or thousands of light-years from Earth (not counting the Sun itself, which in 5–6 billion years will become a planetary nebula and then a white dwarf).

The Good Friday Eclipse

The three Synoptic Evangelists report that at the death of Jesus, the sun was darkened: “At the sixth hour darkness came over the whole land,” writes Mark (15:33). Matthew and Luke record this phrase with only minor variations (Mt. 27:45; Lk. 23:44). Luke adds an absolute genitive (tou hēliou eklipontos, τοῦ ἡλίου ἐκλιπόντος) that is understood as a reference to an eclipse: the verb ekleipō means “to fail, to cease,” but when used with the sun (as here), it means “to be eclipsed,” hence “as the sun was eclipsed.”

As universally acknowledged, it is impossible for a solar eclipse to have occurred on the day of Jesus’ death. The Jews used a lunar calendar in which the month began with the new moon. The Jewish Passover always fell on the 14th of Nisan (the spring month corresponding to March–April), during the full moon, when a lunar eclipse is possible—but not a solar eclipse, since the moon is in opposition to the sun at that time.

It is no coincidence that the account is found in Mark, who was almost certainly writing in Rome and was not very familiar with Jewish customs. It is unsurprising that Matthew confirms and adds other supernatural elements of his own—such as the earthquake and the saints rising from the dead. It is, however, somewhat surprising that Luke—a cultured man who had conducted research—did not recognize the impossibility of a solar eclipse occurring under those circumstances.

Judas Sitting on the Throne of Glory

Eucharist

What Language Did Jesus Speak?

Jesus spoke Aramaic, a language of the ancient Near East. More specifically, he spoke the Palestinian Aramaic dialect of Galilee, which differed from the Palestinian Aramaic of Jerusalem mainly in certain pronunciation features. This is also reflected in the Gospels, where Peter is recognized because of his accent. It is possible that Jesus also knew Greek (which would explain how he could converse with the Syro-Phoenician woman in the episode recounted by Mark and Matthew), and he almost certainly knew Biblical Hebrew (as Luke depicts him reading a passage from the prophet Isaiah in a synagogue on the Sabbath and then commenting on it).

In the Gospel of Mark, sixteen words or short phrases of Jesus are reported in Aramaic, though not all are rendered accurately.

Aramaic is a Semitic language, like Hebrew, Arabic, Ethiopic, as well as Assyrian and Babylonian—and before them, Akkadian. These are consonantal, paratactic languages written from right to left using alphabetic scripts. Aramaic developed in the late second millennium BCE among nomadic tribes roaming Syria.

It became the lingua franca of the East when it was imposed on subjugated peoples by the Assyrian Empire, and later by the Babylonian and Persian empires. Aramaic thus evolved into a family of languages and was spoken by many peoples across many lands for a long time.

Abraham

Abraham is the father of many nations. His name is composed of ab/av (“father”) and rum (“to exalt”). He had eight sons by three women: Ishmael by Hagar, Isaac by his half-sister Sarah, and six others by Keturah.

His firstborn, Ishmael (Ishmael, “the Lord hears”), is considered the ancestor of the nomadic Arab peoples. The name of his mother, Hagar, is Egyptian and may be connected to the Hagrites, a local ethnic group. Hagar was cast out by Sarah because, having become pregnant by Abraham, she looked down on her. But the angel of the Lord appeared to Hagar at the spring of Shur in the desert and persuaded her to return to Sarah in submission, promising her a great lineage. Ultimately, however, Sarah had Hagar and Ishmael permanently expelled from Abraham’s household.

His second son, Isaac (Yitschaq, “he laughs”), born to Abraham’s beloved and very beautiful wife Sarah, is famous for the well-known episode of the near-sacrifice, in which he plays only a secondary role. He was given as a wife his relative Rebekah, to whom he was an uncle. Sarah (“princess”) is one of Israel’s “matriarchs” for several important reasons: by divine intervention, she became the mother of Isaac, from whom Jacob and the twelve tribes of Israel would descend. She is also the central figure in the story of the sister-wife: she is offered by Abraham as a bride first to Pharaoh and later as a promised wife to Abimelech. Sarah was, in fact, Abraham’s half-sister.

These episodes, which are rather puzzling in themselves, reveal the different periods in which the various sagas of Abraham’s story were composed: there is an “archaic” Abraham, who still follows the strategy of endogamous marriage for himself and his son Isaac; and a “modern” Abraham who, when Pharaoh shows an interest in Sarah, tells him: “No, she’s not my wife, she’s my sister!”

As for his third wife, Keturah (“Keturah”), Genesis mentions only the names of their six sons. The name Keturahcomes from a root meaning dense smoke or vapor.

P.S. Etymologies taken from the Brown-Driver-Briggs lexicon.

The Language of Abraham

The Assyrian Royal Inscriptions

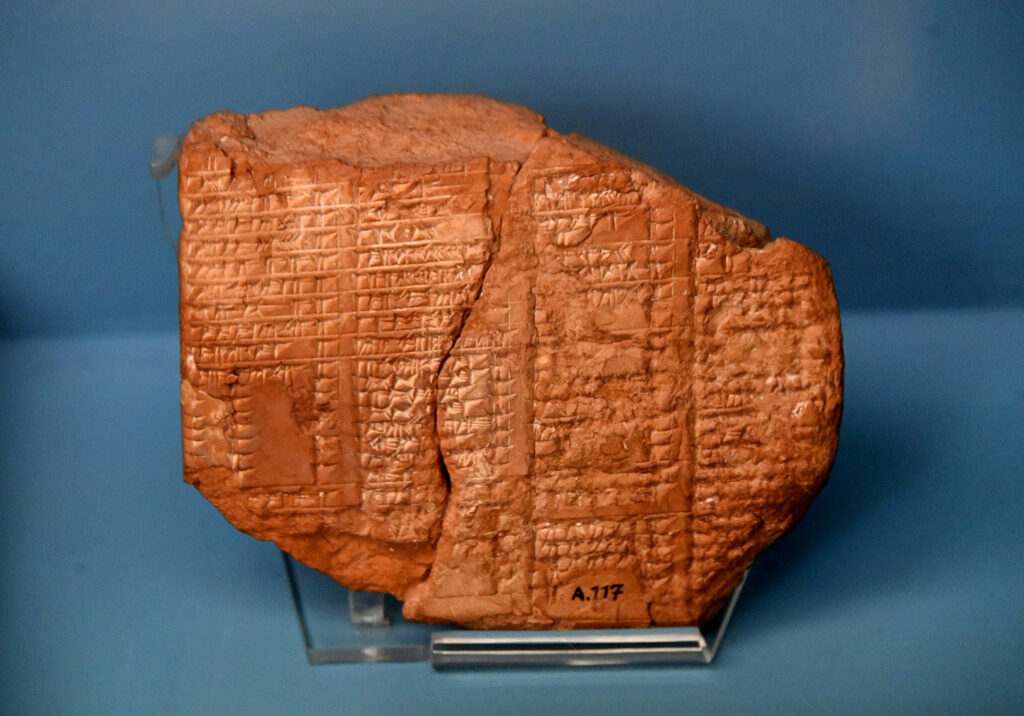

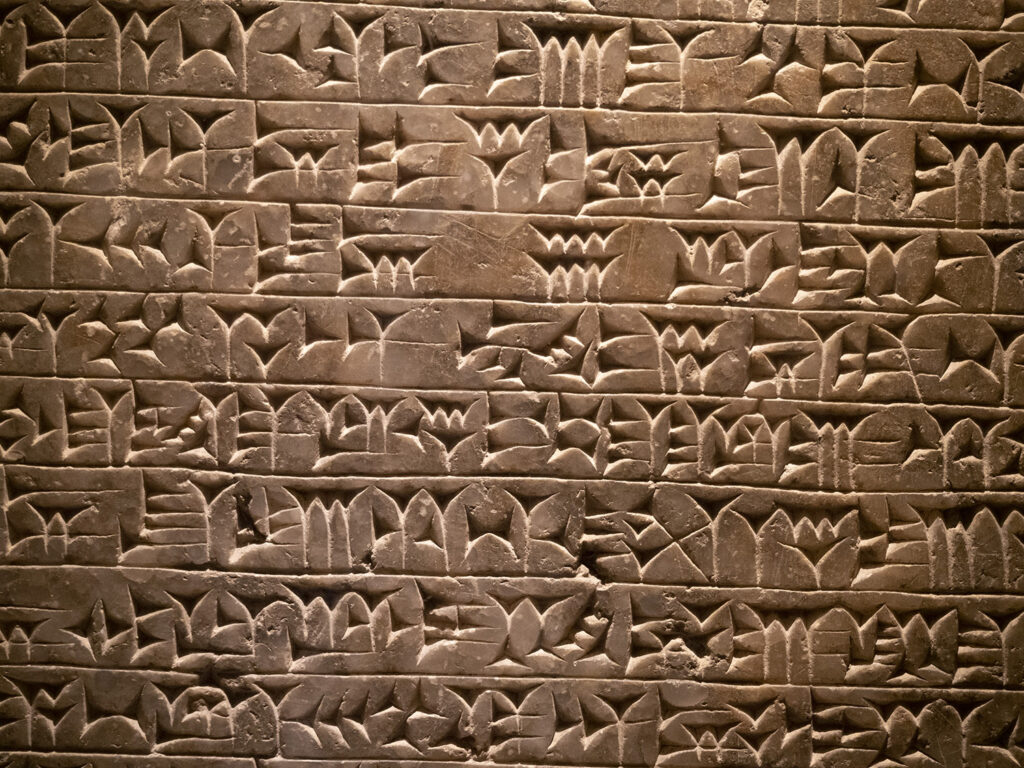

The Assyrian King List is a list of Assyrian kings compiled by the Assyrians themselves over the course of their millennia-long history. It has come down to us in three copies and two fragments, all fairly similar to one another.

The earliest kings, described as “those who lived in tents,” date back to the late third millennium BCE. The last king recorded in the lists, Sin-shar-ishkun, died in 612 BCE, the year Nineveh—the Assyrian capital—was captured by the Medes (ancestors of today’s Kurds) and the Neo-Babylonians (i.e., the Chaldeans), following a rebellion war that lasted four to five years. The date of Nineveh’s fall marks the beginning of the Kurdish calendar.

Immagine da wikipedia.

Author: Neuroforever

License: details

The Ebla Archive

The Mari Archive

The Ugarit Archive

Ugarit was an important commercial center starting around 1900 BCE and remained active until its destruction around 1200 BCE, probably at the hands of the so-called Sea Peoples. It was located on the northwestern coast of Syria and served as a major Mediterranean port; archaeological evidence shows it was inhabited as far back as the Neolithic period. Like all settlements in Palestine and Canaan—which lay along the route between Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia—it was constantly influenced by the dominant empires of the time, especially the Egyptians and the Hittites.

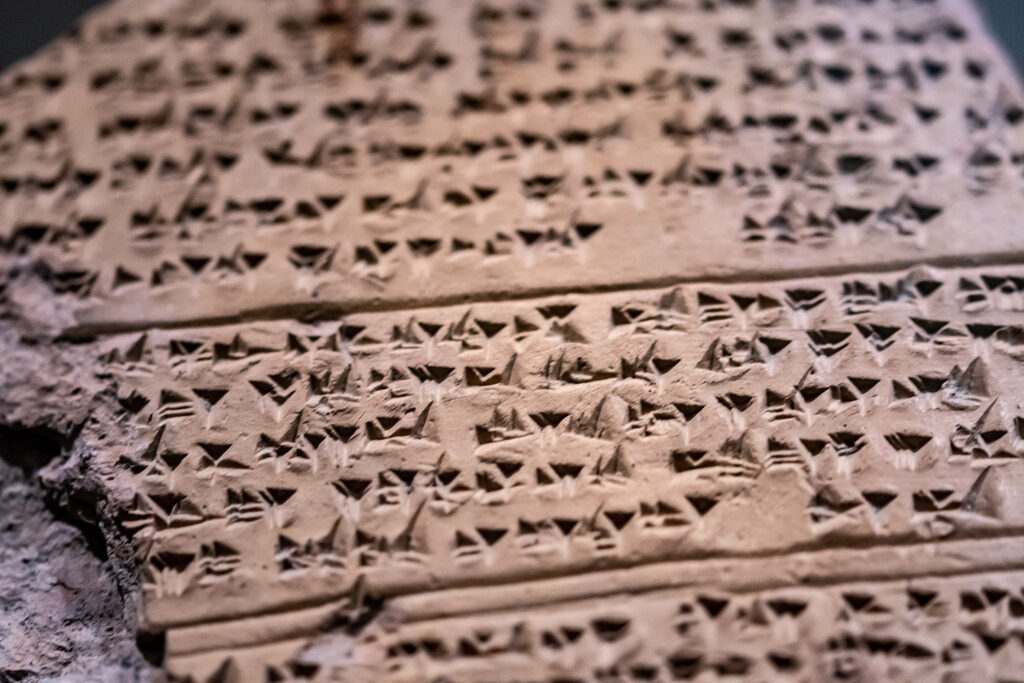

The language spoken in Ugarit was Ugaritic, a Northwest Semitic language that was completely unknown until the discovery of the archive.

The archive, unearthed in 1928, dates to around 1300 BCE. It consists of tablets written in eight languages and four scripts. Of particular note is an alphabetic script using cuneiform signs to represent the 30 sounds of the Ugaritic alphabet. Other artifacts were written in Egyptian hieroglyphs and so-called Hittite hieroglyphs—used respectively for Egyptian and Luwian (an Anatolian Indo-European language)—as well as in cuneiform script for Akkadian and Sumerian (both Semitic languages), and for Hittite and Hurrian, which are Indo-European languages.

This remarkable linguistic diversity reflects the cosmopolitan character of Ugarit, due both to its geographical position and the commercial nature of its economy.

The Amarna Letters

The Scripts of the Ancient Near East

© 2025 Federico Carra. All rights reserved to the author..